If it feels like Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) is everywhere these days, that’s because it is.

According to research from Cornerstone Advisors, the percentage of Gen Zers in the U.S. using BNPL has grown six-fold from 6% in 2019 to 36% in 2021. Millennials’ use of BNPL has more than doubled since 2019 to 41%. Gen Xers’ adoption more than tripled. And Boomers use of BNPL has increased from 1% to 18%.

Collectively, this usage in 2021 will translate into nearly $100 billion in retail purchases — up $20 billion from 2019

Based on these numbers, it can be easy to conclude that BNPL is inevitable — I recently made that very argument myself — however, it’s important to remember that new solutions often feel that way at the beginning.

Take credit cards as an example. Today merchants’ antipathy for credit cards (interchange fees, specifically) is well-established. Yet when Bank of America introduced the modern credit card in 1958, merchants loved it and were more than happy to accept them at a 6% fee (two to three times what interchange fees are today), as Joseph Nocera relates in his bookA Piece of The Action How The Middle Class Joined The Money Class:

[Kenneth] Larkin [a long-time Bank of America executive] remembers visiting a drugstore, hoping to persuade its owner to accept BankAmericard. "When I explained the concept of our credit card," he says, "the man almost knelt down and kissed my feet. 'You'll be the savior of my business,' he said. We went into his back office," Larkin continues. "He had three girls working on Burroughs bookkeeping machines, each handling 1,000 to 1,500 accounts. I looked at the size of the accounts: $4.58; $12.82. And he was sending out monthly bills on these accounts. Then the customers paid him maybe three or four months later. Think of what this man was spending on postage, labor, envelopes, stationery! His accounts receivables were dragging him under."

A store owner who accepted the card was, in effect, handing his back office headaches over to the Bank of America. The bank would guarantee him payment — within days instead of months — and would take over the role of collecting from the customers. As for the bank, in addition to taking its 6 percent cut, the card was a way to get its hooks into businessmen who were not yet Bank of America customers.

Credit cards took off, in large part, because they solved an urgent back office problem for merchants. It took a while for the problems with credit cards — for both merchants and consumers — to become clear and to motivate people to search for new solutions.

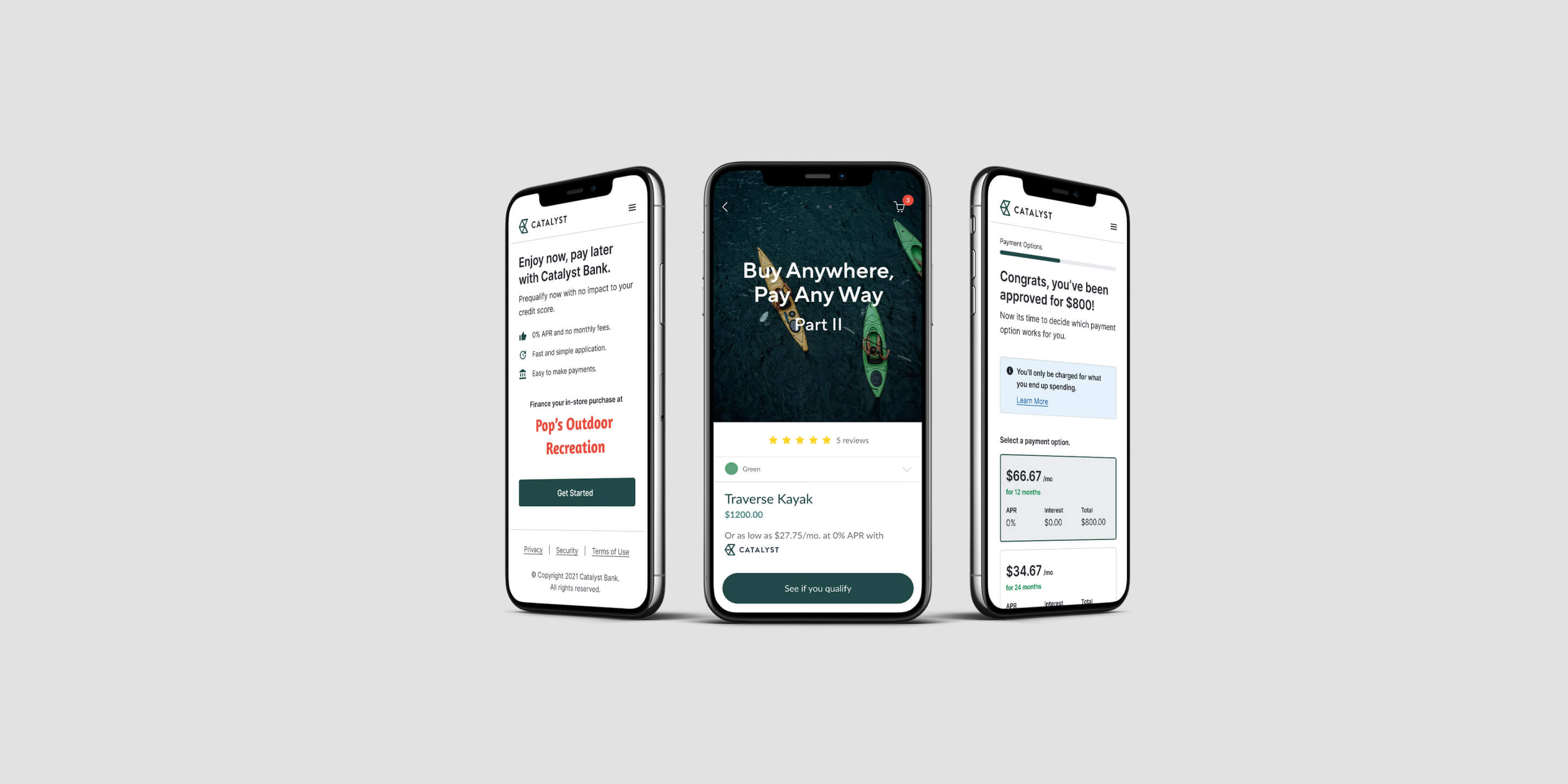

BNPL has taken off, in large part, by solving an urgent sales problem for merchants. Shopify, for example, found that one out of four merchants saw a 50% higher average order volume with its BNPL product. Consequently, merchants are happy to pay anywhere from 2% to 8% of each transaction in fees for this BNPL-powered sales lift. That’s where we are today.

However, I think it’s worth looking forward a bit and making some educated guesses on where the problems with BNPL — for merchants and consumers — may emerge because, like with credit cards, those problems will eventually drive the development of new solutions.

BNPL Gaps for Merchants

Cost

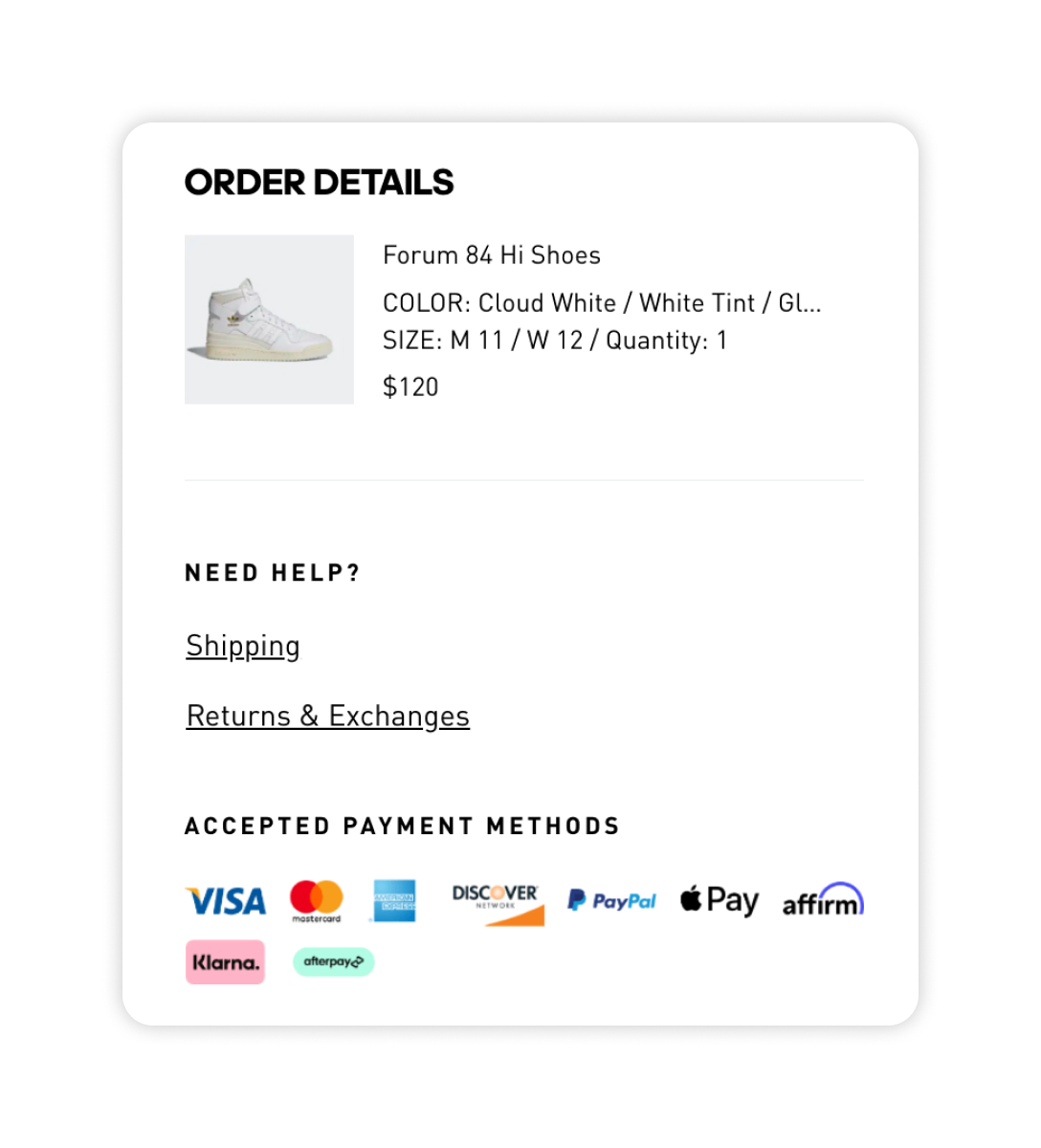

The easiest problem to analogize to credit cards, the costs of BNPL will eventually become a concern for merchants once they become inured to the sales benefits that it provides. We already see some merchants beginning to treat BNPL providers more like vendors and less like partners, pitting multiple providers against each other and (I imagine) using the results to drive down costs over time. Here’s what Adidas’ checkout page looks like:

Competition

Another challenge for merchants in partnering with the big BNPL providers is the fact that those providers aren’t, in most cases, white-labeled. When a consumer buying a pair of shoes from Adidas uses Klarna (for the first time) to finance the purchase, Klarna works extremely hard to convert that new customer into a repeat Klarna customer. Klarna’s goal, in doing this, is to get that customer to start the shopping process in its mobile app, which gives Klarna the ability to steer that customer toward specific merchants. Klarna (and other big BNPL providers) has begun to monetize that steering through its affiliate marketing business, as Klarna’s President of North America David Sykes explained:

These brands are paying affiliate marketing fees of anywhere between five and 15 percent. The cost of acquiring a customer on Facebook or on Google could be anywhere between $50 and $100. So, in that context, Klarna, as a source of new customers, is actually extremely competitive. We really try and drive customers to our retail partners.

Essentially, BNPL providers are selling merchants’ customers back to them. You can see how, long term, this might be a cause for concern.

BNPL Gaps for Consumers

Financial Health

BNPL providers like to claim that their products are a superior option to credit cards for consumers that want to get periodic access to credit without going deeply into debt. However, like credit-card issuers, BNPL providers are financially incentivized to encourage consumers to spend, and there is emerging evidence that consumers’ BNPL-enabled spend is starting to impact their overall financial health.

According to research from Cornerstone Advisors, over the past two years, 43% of BNPL users made late payments.

More interesting, however, is why they were late in making their payments. According to Cornerstone’s research, only one-third of these consumers blamed the late payment on not having enough money to pay their bill. The majority (two-thirds) placed the blame on losing track of when the bill was due.

What this tells us is that the proliferation of BNPL loans — which is expected to continue accelerating — is making it significantly more complex for consumers to manage their financial obligations.

Credit Invisibility

Due to their short duration and lower dollar amounts, pay-in-4 BNPL loans, offered by providers like Klarna and Afterpay, are a great product for new-to-credit consumers. And, indeed, many of the consumers that frequently use Afterpay and Klarna do so specifically because BNPL is the most accessible, low-cost form of credit available to them.

This should make BNPL the ideal on-ramp for the 45 to 60 million credit invisible consumers in the U.S. to start building positive credit histories and get access to other mainstream credit products.

But it doesn’t.

Today, most BNPL companies don’t report repayment data to the U.S. credit bureaus, and even those that do don’t report data to all three credit bureaus. The result is that even if a consumer is paying back their BNPL loans on time (not a guarantee, as we’ve already discussed), it won’t translate into a thicker credit file or higher credit score.

Room for New Solutions

BNPL is here to stay. But that doesn’t mean that the current BNPL products in market are perfect. Nor does it mean that the dominant BNPL providers in the market are unassailable.

Quite the opposite.

There are numerous gaps within the design of current BNPL products and business models that can be exploited by banks, but only if they build BNPL offerings that are meaningfully differentiated from the options that consumers and merchants are choosing between today.

The question is — which banks are ready to compete?

To learn more about BNPL and how to find the right fit for your organization, read our recent post "Buy Now, Pay Later Partnership Models: Which is Right for your Financial Institution?"

Read Article

Read Article